The Basics of Anti-Aliasing

How images are rendered

Imagine your computer is rendering an image of a tomato on top of a table. In order to render the image each of the 1920 * 1080 pixels on your screen needs to have colors assigned to them. This isn’t as easy as viewing a video or an image. The tomato can be viewed from any angle, and the pixels will need to be recalculated many times every second to produce a smooth animation.

A GPU must calculate samples in order to show you an image. A sample is a light/color calculation that can be thought of as an infinitesimally thin ray of light. Imagine that you have a bunch of these rays of light, and pretend these light rays are 1-dimensional objects - lines - that are going straight through your screen. For those familiar with optics this is called normally incident. Most often each pixel will get one ray of light.

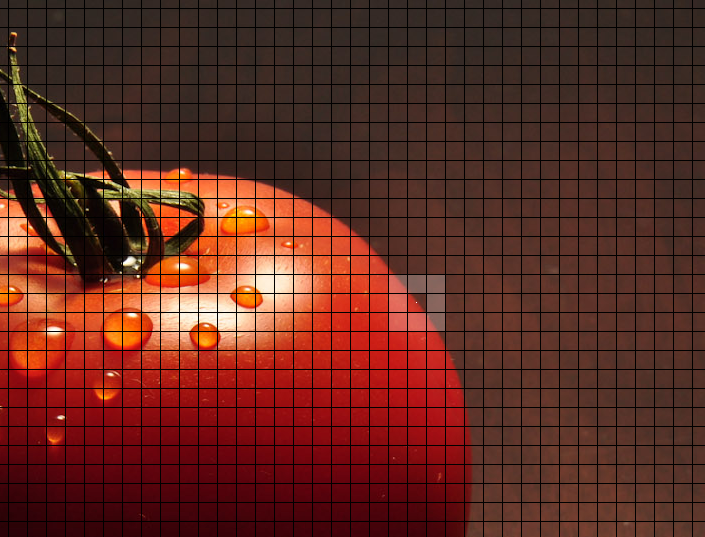

Most often your computer runs a single one of these rays through the middle of a pixel (the surrounding pixels in that image are highlighted to make it easier to see the sample). When one of the rays hits an object in the game, it bounces off and goes back through the same pixel it came from, this time with the color of the object it hit. That ray then determines the color for the whole pixel.

Why AA is needed

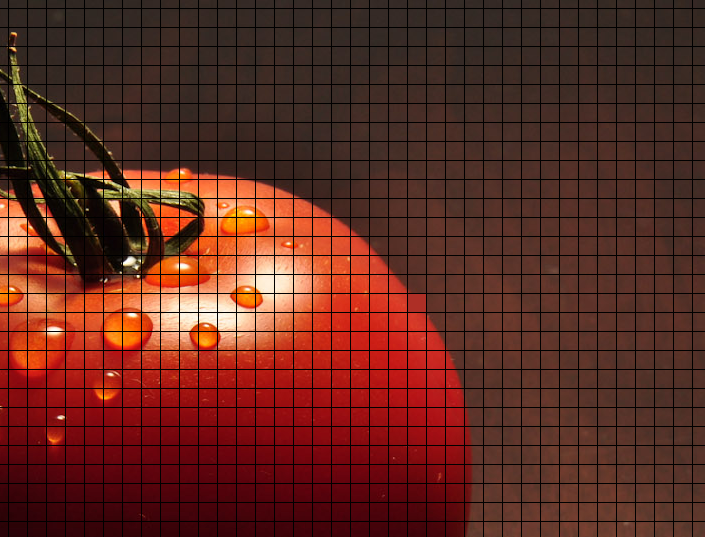

Now most of the time this works pretty well. If you have two pixels from the same object that are right next to each other - like two pixels on the inside of our tomato - they’ll have pretty similar colors and the image will look smooth. However, when you reach the edge of this tomato, you’ll eventually find a pixel is no longer over top of the tomato.

The pixel on the left will be red like the tomato, but the one to the right of it will be brown like the table it’s on. The difference in color is dramatic. The pixels are either on the tomato or not, there is no middle ground.

The problem here is that the pixels don’t accurately represent what’s going. If you look at the “pixels” drawn over the image of the tomato you’ll see that the area covered by the some of pixel has too much information to be conveyed by a single ray of light. On the right half of the pixel there’s the table, and on the left half there’s the tomato. Other pixels contain significantly less information. The pixels in the upper left corner of the image have fairly uniform colors throughout them, so when they are reduced to a single sample there is less information loss.

The solution programmers have come up with this problem is what we call anti-aliasing. The game engine takes more than one sample per pixel (either one in each corner of the pixel, a few different samples in a grid formation, or sometimes even in random locations). Some will hit the tomato and some will hit the table. The colors are then averaged together to give you your final pixel color.

Types of Anti-Aliasing

The method of AA that’s the simplest to understand is called super sampling anti-aliasing (SSAA). It simply takes more than one sample in every pixel on the screen. Because sample calculations take a while to do, this form of AA is extremely taxing on your graphics card. You’re essentially rendering the same screen multiple times.

Another form of AA is called multi-sampling anti-aliasing (MSAA). This form of AA has an intelligent algorithm that finds out what pixels need more than one sample, and then simply does more samples on those pixels. This form of AA is much cheaper than SSAA and is also a lot more popular. MSAA doesn’t work well for all games. Minecraft is the best example of a game where the edges of objects aren’t the only thing that needs to be anti-aliased. Take a look at the insides of block textures. The game doesn’t blur anything inside of blocks like most other games do, so SSAA is the best option for Minecraft.

There are other forms of AA, but these two are the simplest to describe.